2008, series of 7, screenprint

on gold-plated MDF, 100 x 100 cm,

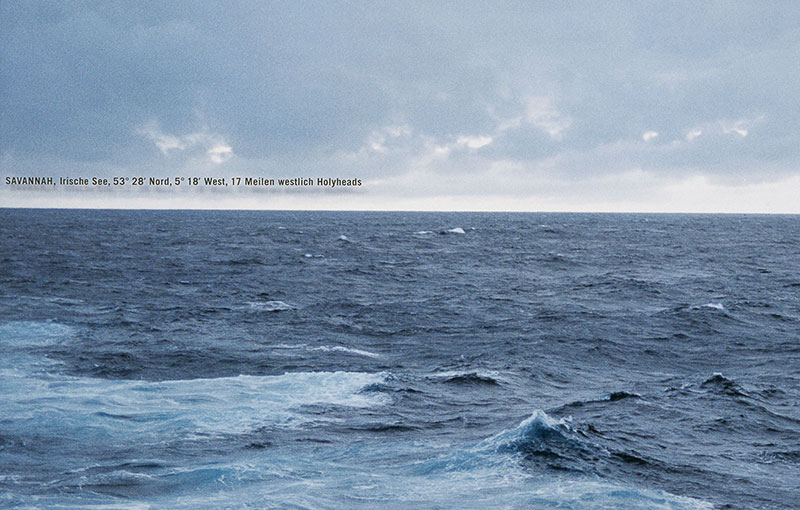

5 b/w photographs, each 24 x 30 cm, framed,

one text, screenprint, 24 x 18 cm, framed

Photo exhibition view: Nick Ash, KLEMM’S, Berlin, 2010

In the summer of 2007, a group of 14 cartographers went on a walking tour across five Polish moors—a venture which required courage, a love of nature and, of course, precise knowledge of the territory. None of the men was older than 30.

more

The cartographers’ base, this year’s “summer camp” was near Braniewo, formerly Braunsberg. The cartographers pitched their tents on an elevation not far from the old Reich highway Elbing-Königsberg. The concrete roadway ran through the forest, unused and forgotten. Luckily, the cartographers had detailed maps from the year 1938. Still, when they left the trail they got lost twice.

From the camp there was a magnificent view of a lagoon and fields where the corn was already standing high and strong. They admired the rye—“taut and thick, like a horse brush.” Or the meadows “where the cuckoo flower flashes exquisitely pink between the high grasses” and “the enticing splendor of yellow marsh marigolds” along the ditches. And further in the distance: “the forest, so dense, the solemn darkness of the spruce.” On the evening of July 20th, they raised the black-and-white East Prussian flag.

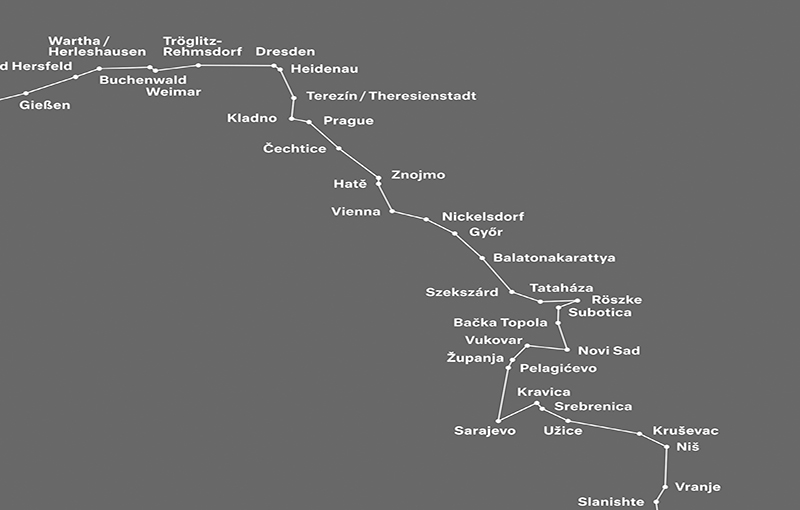

In the mornings there was always a ceremony with Eichendorff, Hölderlin, Kleist’s “Germania to her Children”, followed by the hymn, sung softly, “Day has broken over lagoon and moor. Light is risen in the East.” A map was unrolled. The lovely names of the places: Tannenberg, Allenstein, Cadinen. And of course Marienburg. All in vain.

At night, they went off to the moors. There they waited “for the sun to burn a hole in the clouds of night, for the moor to awaken, throw off the veil of mist and begin to speak clearly with the song of the lark, the beat of the meadow pipit’s wing and the curlew’s whistle.”

And at that same moment, the cartographers began to speak clearly too—of lost villages, vanished towns. They spoke of places that no longer existed. Of places they knew only from their maps. They spoke of the homeland and the misfortune of being born too late. There they stood, knee-deep in the mire, pining for home. less

From the camp there was a magnificent view of a lagoon and fields where the corn was already standing high and strong. They admired the rye—“taut and thick, like a horse brush.” Or the meadows “where the cuckoo flower flashes exquisitely pink between the high grasses” and “the enticing splendor of yellow marsh marigolds” along the ditches. And further in the distance: “the forest, so dense, the solemn darkness of the spruce.” On the evening of July 20th, they raised the black-and-white East Prussian flag.

In the mornings there was always a ceremony with Eichendorff, Hölderlin, Kleist’s “Germania to her Children”, followed by the hymn, sung softly, “Day has broken over lagoon and moor. Light is risen in the East.” A map was unrolled. The lovely names of the places: Tannenberg, Allenstein, Cadinen. And of course Marienburg. All in vain.

At night, they went off to the moors. There they waited “for the sun to burn a hole in the clouds of night, for the moor to awaken, throw off the veil of mist and begin to speak clearly with the song of the lark, the beat of the meadow pipit’s wing and the curlew’s whistle.”

And at that same moment, the cartographers began to speak clearly too—of lost villages, vanished towns. They spoke of places that no longer existed. Of places they knew only from their maps. They spoke of the homeland and the misfortune of being born too late. There they stood, knee-deep in the mire, pining for home. less